Western man’s fascination with appearances dates from the time of the Greeks. In the latter half of the fifth century B.C., the painter Apollodorus, who is credited with the invention of the use of tone to depict forms as volumes, initiated the quest which has informed all illusionistic efforts in western painting. Plato condemned the work of Apollodorus as illusion and deception, a criticism which has rung through the centuries whenever painters have resorted to trompe loeil…the French phrase which means to deceive the eye.

Legend has it that the painter Zeuxis won a contest when his painting of grapes deceived birds into pecking at the surface of his painting. Outdone, the painter Parrhasius invited Zeuxis to his studio to view a painting which was hidden by a curtain. Zeuxis attempted to draw the curtain aside, only to find that he had been tricked by the more than real representation of a drape painted by Parrhasius.

Western man has been long besotted with the tricks and devices of illusionist painters. The Orient has smugly quested after the spiritual and divine…thinking we were primitives easily distracted by the appearance of gold, and upon whom the real thing was wasted. Our greatest artists, however, have achieved that plane upon which noble sentiments and naturalism wed in statements of monumental beauty and spiritual meaning.

History does us a great service. Minor hacks and mediocre efforts get left by the way; only the finest works tend to survive. The culling, in our own time, is left to us. To be able to separate the important work from the shallow and merely derivative, to know good from bad requires a substantial education. Such an education must be coupled with an almost spiritual power of intuition, a sense of one’s time and a knowing appreciation of an artist’s integrity: No small challenge.

For nearly a century we have had a succession of movements burst upon the art scene…each with its own strident manifesto. So rapid an avalanche of competing ideas and theories could only generate confusion and uncertainty. This ferment of competing claims and notions has enriched the vocabulary of art; however, it remains for a grand master to bring about an order which will unify this fragmented excitement, a grandmaster who will produce a body of work which will integrate and give meaning to this series of paper tiger revolutions.

Contemporary art teaching has been bewitched by the Bauhaus and buffeted by a sequence of trendy changes in the marketplace. In consequence, art instruction has turned away from the wisdom of the ages…a heritage which concerned itself with naturalism, figuration and the images of men and the world in which men live. The heritage of western art is one which concerns itself with man’s own image, but it is not a tradition which concerns itself with appearances.

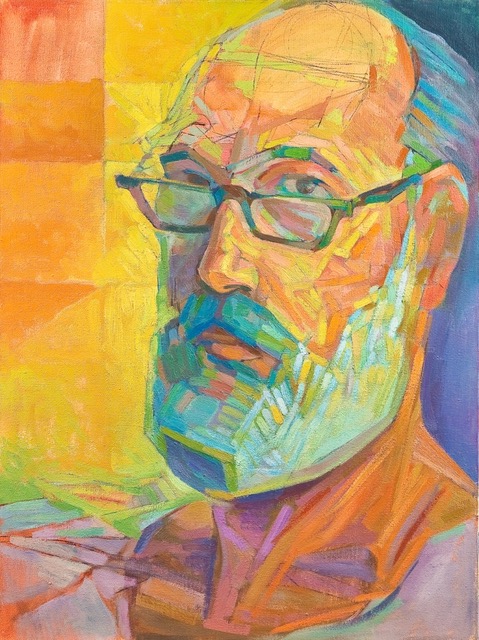

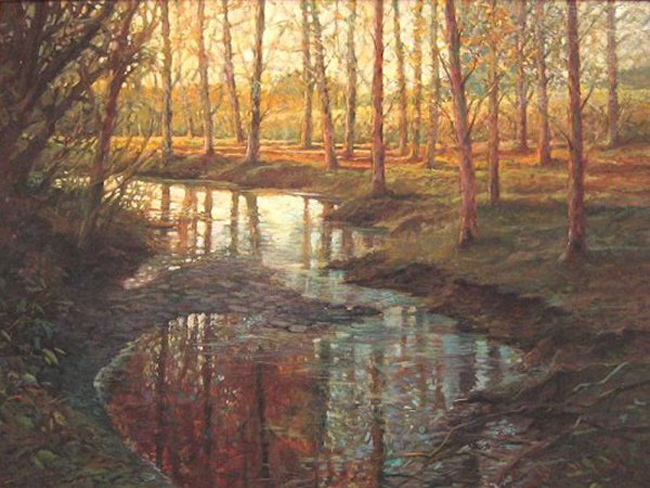

Through the ages artists have translated these appearances into the language of form, forms based upon principles of design, canons, rules, and modes of order which bring structured meaning to the chaos of mere appearance. The intellect and sensibility of each artist was the altering filter through which recognizable images were transformed to express views and feelings, ideals and joys. Such a tradition elevated the artist from a base recorder of facts and demanded that his work be creative transformation, vision, and prophecy.

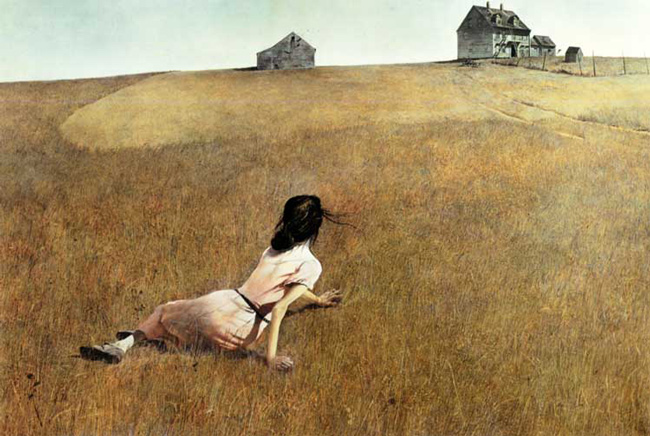

Today, most unexpectedly, from the point of view of art critics, museum directors and many trendy collectors, there surfaces a tidal wave of interest in Realism, a notion these self-appointed purveyors of taste had unanimously ignored.

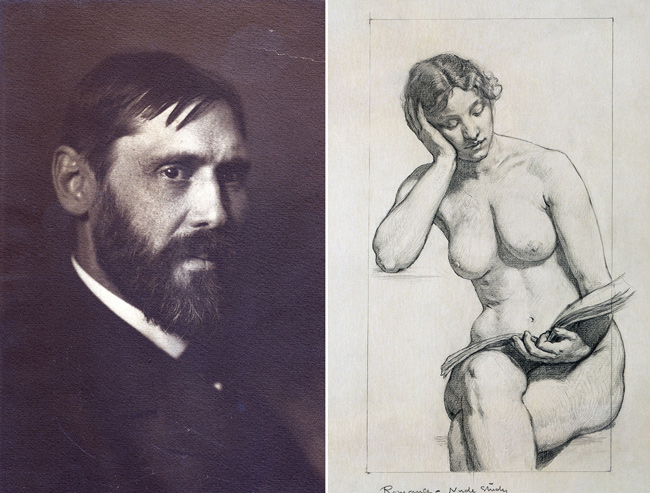

This New American Realist movement has been launched by the Pennsylvania Academy of Art. The exhibition has brought together the works of middle-aged artists who have maintained a link with early American trompe loeil painting: A hodgepodge of eccentric styles superficially related by a common concern with the photographic image.

This garden-variety interest in the photographically accurate recording of detail has never been a concern to serious painters. To admit such a quest would rule out the significance of the artist altogether. Expressive and interpretative rendering of form requires distortion and deviation from the norm. The true artist intervenes, altering and adjusting the pedestrian view to convey a philosophy, which, if effective, will awaken in the viewer an awareness of revelation.

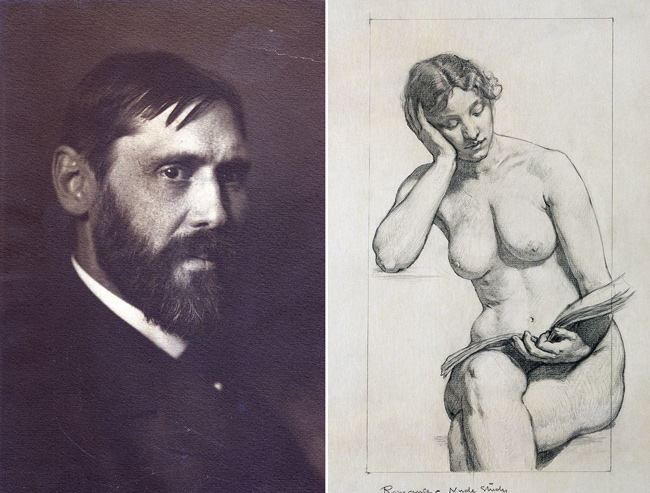

The tyranny of detail preempts artistic intervention. Kenyon Cox has said, “without design there may be representation, but there can be no art”. The word design embraces that sphere which we recognize as adjustment, alteration, and deviation. Design is structure, order…an imposed program: That sphere which allows for interpretation.

Much recent art instruction has been in hot pursuit of the latest trend and innovation. The battle cry has been: There are no rules, anything goes…express yourself. This event…the return to figuration/naturalism, has caught many a modern painter ill-informed, with little or no training in the skills and understanding he now dearly requires. This is the context within which I explain the particularly primitive works gathered at the Academy. Every indication promises that we are about to see a return to teaching methods and disciplines that have not been part of the scene for many a year…the need is blatant and there is now a focus which will demand serious instruction.

Man’s ancient need to translate his feelings and ideas into images with which he can closely identify can never be restrained for long. Before American figurative painting can find a strong voice a vacuum must be filled. Perhaps this growing interest in realism will cause a return to sound classical drawing practices. Perhaps we are about to see a return to structures of form and order in naturalistic painting. Perhaps a new and vital American Realism is gathering its forces to express our time and country in the grand tradition of western painting.