“He called himself a carpenter; he was, in fact, a cabinetmaker. Mr. Griffith discarded lumber he regarded as inferior. He would cut a board, and test it, and take off a little more with his plane, and finally, he would fit the board precisely. He cut every mortise as if he were a jeweler cutting the facets of diamonds. He sandpapered; he polished; he filled every nail hole. He made square corners. He cared.” —James J. Kilpatrick, The Writer’s Art.

Yes, Mr. Griffith cared. He had a standard against which to measure his efforts. Not only did he care, he knew. He must have been well trained.

In our day there has been a liberation of feelings; narrow self-interest has been encouraged, and few people admit to the proliferation of shoddy work. If you feel good about what you do, you are blessed. Anyone daring to suggest ways of improving the work of another risk social suicide.

Nowhere is this public display of private feelings more apparent than in the art class. The art teacher must be one of the more compromised by this social phenomenon. How can one offer critical suggestions to a ‘student’ who is experiencing personal fulfillment from fatuous work? The conditions which obtain in most art classes resemble those of a mental institution, where inmates are humored in the fragile hope of improvement.

In the June 1984 issue of ‘Time Magazine,’ the respected art critic Robert Hughes reviewed an exhibition of drawings from the Victoria and Albert Museum: “Such nuts and bolts are laid out with unfailing clarity: all the technical stuff one thinks one knows but is hazy about is there. It is reported that 20% of Americans are illiterate, and 45% say they never read books: so it is not too dyspeptic a guess that 99% cannot read a drawing.”

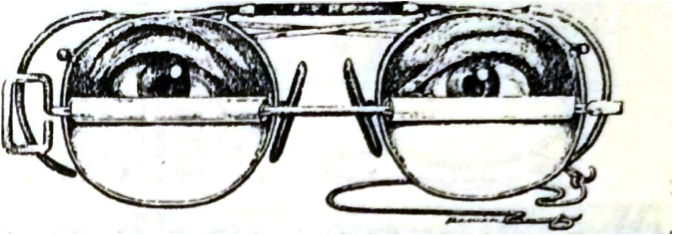

Graphic languages consist of coded marks. The untutored are most unlikely to decipher these on their own, and our times discourage quibblers who concern themselves with the technicalities of proper usage. However, if one is unable to read a drawing, one cannot hope to understand artworks of any kind; drawing is the basic language of all design.

If 99% of Americans are unable to read a drawing, we must turn to our schools to discover why. We shall find that art, the fine arts — the nuts and bolts of the language, is rarely taught, and drawing. . . almost never. Crafts are taught. Something like illustration or commercial art is taught. Crafts and commercial art are not art.

A drawing of an apple is not to be confused with an apple. The standards which determine the quality of an apple are not those by which one evaluates a drawing; drawing is not about appearances. An ignorant but faithful copy of an apple is not a drawing.

In few schools, public or professional, will one find drawing taught with respect or understanding. Mr. Hughes has reason to lament. Mr. Kilpatrick has reason to nostalgically describe the work of a fine craftsman, hoping to excite young writers to toil with purpose at the code used to represent our spoken language.

If, as many believe, we mostly get what we deserve; Americans are content with the low standards in art teaching. Art teachers are pleased with the quality of their training, and most art school graduates are untroubled to be numbered among the 99% of Americans who cannot read a drawing.”

From: GLIMPSING A LOST ATLANTIS, by Robert Hughes, Time Magazine’, June 11, 1984

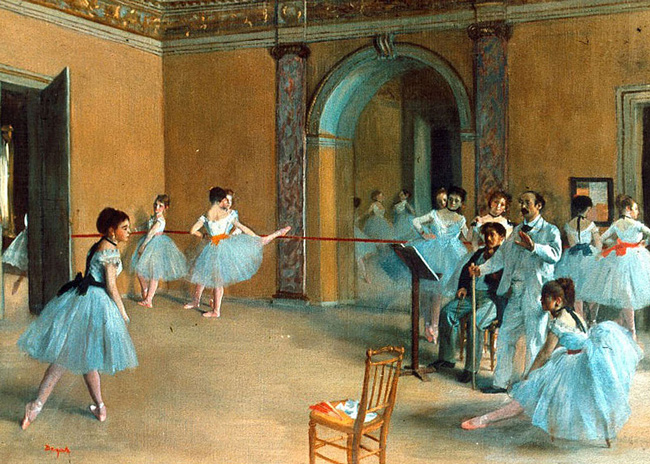

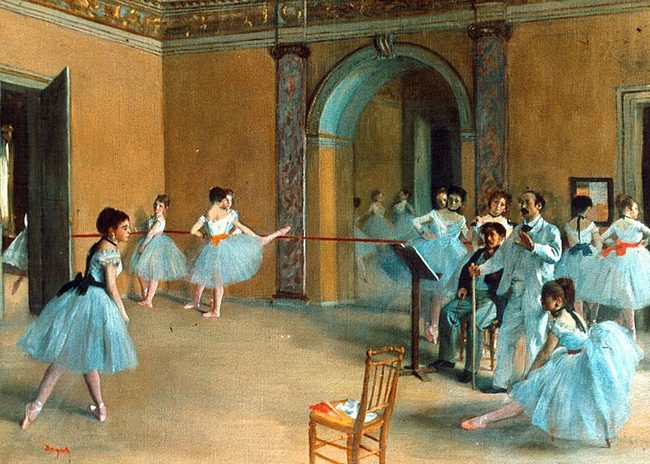

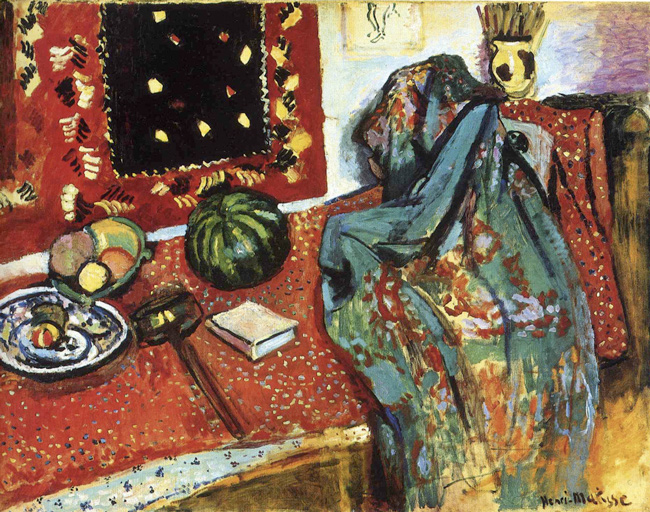

The exhibition called “Reading Drawings” that is now on view at the Drawing Center is as elegant a teaching show as one might wish to see. Why study drawings at all? Because they are often the clearest index to a painter’s intentions; finished or fragmentary, they are the deposit left by the process of image forming, the residue of the dartings and probings that constitute pictorial thought. A century ago, most educated people drew as a matter of course because it was the best way to remember what they saw. Great Aunt Lucinda with her watercolor set, earnestly dabbling in the shade of the Duomo, may have been a figure of mild fun; but she (multiplied by tens of thousands) was also the ground from which the tremendous graphic achievements of a Degas or a Matisse could rise. Such amateur experience added up to a general recognition that to draw, to reconstitute a motif as a code of lines and tonal patches, is to think, and that such thought forms the root of all visual literacy. A stroll in SoHo today, by contrast, will furnish any number of artists who can barely trace, let alone draw. Was the long-derided practice of drawing from plaster casts rather than the living model really as deadening as we were once told? Assuredly not, as anyone can tell from the almost terrifyingly obtrusive student drawing of a plaster foot by the future English academician, Sir Luke Fildes.

“…without design there may be representation, but there can be no art.”

—Kenyon Cox, The Classic Point of View