“One truly understands only what one can create” ~ Giambattista Vico (1668 – 1744)

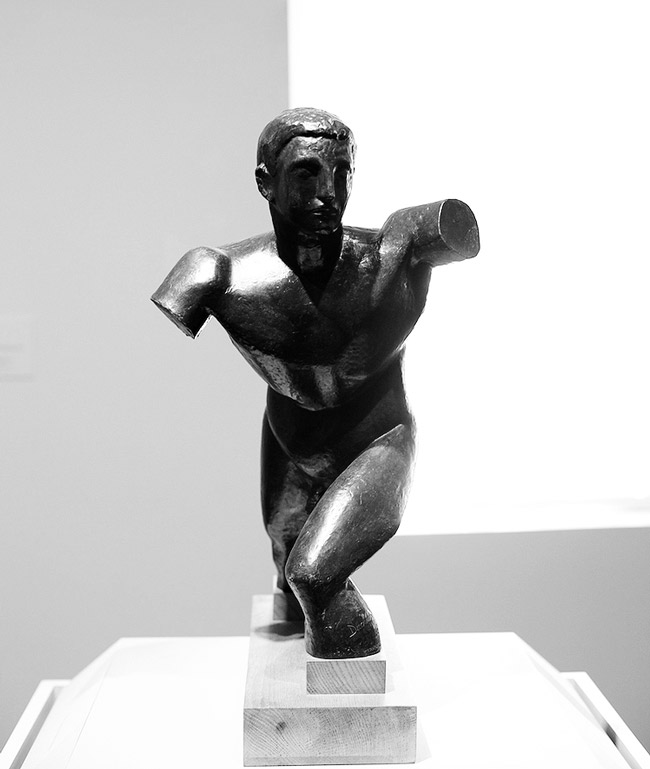

In his monograph on modern sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon, William C. Agee quotes this exceptional artist as having said, “I do not believe that each epoch creates all parts of its aesthetic, but that it finds its roots in the preceding generations which have prepared the way.” Agee continues by describing the sculptor: “A child of French rationalism, Duchamp-Villon placed himself in a long line of artists from Poussin, Ingres, Puvis de Chavannes and Seurat who called on the nobility of the past as a viable basis for a modern art.”

Such views abound in written works by and about great artists. It is from such a body of tradition that I draw my belief that there are constants which remain central to the thinking of all periods and which lend substance to each important new movement. It is these constants which have given continuity and order to great art; which have assured an acute relationship to man’s deepest needs, feelings and thoughts.

At the Studios, an effort is being made to offer a view of the elements and visual considerations which have held the design together. In the Foundation Course in Drawing and Design, Drawing I, a program of studies has been formulated to introduce newcomers to many of the visual concepts and ideas — constants — upon which artists have built their works.

Current trends in the art world can be confusing: A drawing may consist of almost any combination of materials or media. A fine print may never have come close to the author’s hand prior to the magic moment of signature and numbering. Paintings and sculpture may be indistinguishable. Styles and schools of painting pop up like mushrooms and fade in about as much time. The pace of change is breathtaking

Is it possible for us to reach a point where all this freedom might become mere license? Perhaps we have already arrived at the fascinating stage in which everything is nothing and nothing is everything. Since that may be the case, expect to see a frenzied scramble: A return to basics, a crusade in search of the roots of art, a movement to restore the noble, the spiritual, the elevating, the grand. It is high time we address the need for quality of intention as well as the quality of craftsmanship in the works of our artists.

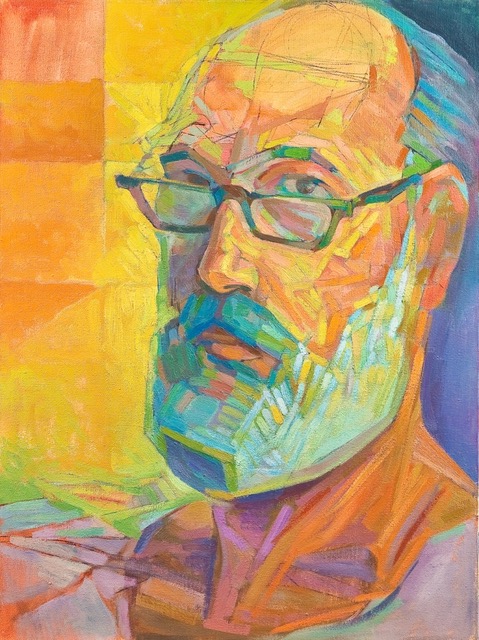

“Only through an intimate experience of the very language used by artists — the language of form — can one hope to gain an appreciation of what the terms employed seek to convey.” ~ Myron Barnstone

Throughout the Western world, drawing instruction in the major art schools reflects a bewildering variety: In one, the model is Raphael; in the next, Matisse or Rauschenberg — in many schools, there isn’t a standard.

In our day, not surprisingly, the teaching of drawing and painting is complicated. A consensus is nigh impossible. The grand old days of the international style are long gone. Each instructor is expected to fashion an approach which is his creative contribution — a situation which produces widely different definitions of art.

One requires a standard and conceptual basis for evaluation. Without a criterion, there can be no means by which we measure the stature of a contribution. At the Studios, we address the thoughts, methods, and pursuits of the outstanding workers in drawing and painting. Their efforts and writings illuminate the structure and inner workings of their art. Our first discovery is that intelligent, orderly development is the rule. To study art is to examine this inner structure; this quest for excellence of expression. Art is not about appearances.

The domain of art is by its very nature mute. Art concerns itself with signs, symbols and visual elements which combine in a silent language. This realm is best approached through direct participation. The key to understanding is not to be found in words — however necessary words may be to our quest.

A drawing instructor is obliged to describe pears with apples. To achieve an understanding in his students, he uses every device at his disposal: Terms are borrowed from the disciplines of geography, poetry, music, science, cookery. Only through an intimate experience of the very language used by artists — the language of form — can one hope to gain an appreciation of what the terms employed seek to convey.

Slowly, a bit like a mysterious revelation, recognition is achieved — a rather lovely event for both learner and instructor. In many ways, art teaching may be likened to spiritual instruction: Personal experience alone leads to comprehension. Such a comparison need not be taken too far. In art teaching, at least, experiences can be contrived and the interested student will learn to see — to understand.