I went to The Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, England. It wasn’t part of Oxford University; it had some affiliations but it was really a finishing school for English debutantes who wanted to meet and marry young undergraduates who had Lords for fathers. They all had thick ankles with peaches and cream complexions. They all had private school educations. They were extremely intelligent and they were the majority of the school…except for six ex-military American G.I.s, some of whom were retired officers in their 50s and 60s. It was a really strange mix!

I arrived at Oxford late in the afternoon. I had taken the train from South Hampton to London and from London to Oxford. When I got off at the Oxford Station, a Victorian relic, I spotted the line of cabs. I asked a cab driver to take me to the Ruskin, little knowing that the Ruskin, at that hour, wouldn’t be open. Also not knowing, that even if it had been open, they didn’t have dormitories.

The fellow who was driving the cab was working class. The only “Ruskin” he knew was a Ruskin school for working men, so he took me to Ruskin College instead of Ruskin School of Art.

I arrived and spoke to the hard-of-hearing housemother, who said she was expecting an American that evening. So when I showed up, she showed me to the room that was reserved for the Yank. I was exhausted from the train, and finally in a place where I could wash up and get to bed. I crashed.

In the morning, I woke up and walked through the corridor, asking where the dining room was. All the pictures on the walls were photographs and reproductions of drawings of men with Victorian and Edwardian mustaches and beards. It didn’t make any sense. There are no artists that I recognized. Looking around the dining room I expected to see recent high school graduates. Most of them were in their 20’s and 30’s, and some were as old as 60. I walked over to a long table and sat down. I listened to so many working-class accents: Yorkshire, Lancaster…the various boroughs of London. These weren’t the aristocratic students from private schools sitting at the table. They all came up from the floors of factories. Through their intelligence, skill and acumen they had won scholarships to Ruskin College, a workingman’s college.

When they learned I had come to The Ruskin to study art, they thought it was funny as hell that I wound up among them. But the good-natured group took pity on me. They explained that I was too late by about six weeks for finding a room to rent in Oxford. Those who were enrolled at school came up here six months earlier to find and put a payment down on a room. The other graduates greatly outnumbered the space that was rentable. They offered to split up and head out in all directions of the compass and see if one of them could find a room for me to rent. It was incredibly generous of those fellows.

Meanwhile, I explored on my own. The Ruskin was on Walton Street, which became Kingston Road. At the bottom of Kingston Road was a pub called The Anchor. Diagonally across the corner from the pub was a green grocer. There was another shop or two and an alley, Aristotle Lane, that went out into the fields. The meadow sometimes flooded and took you to the Thames. You could rent canoes and walk along the river. About a mile up the river was a pub called The Swan. By English standards, it served pretty good food. Pub food was usually pork pie, with an enormous amount of grease inside a pastry cradling a very small piece of pork. You could get a ploughman’s lunch that consisted of a piece of bread, a wedge of cheddar cheese, some chutney and a beer.

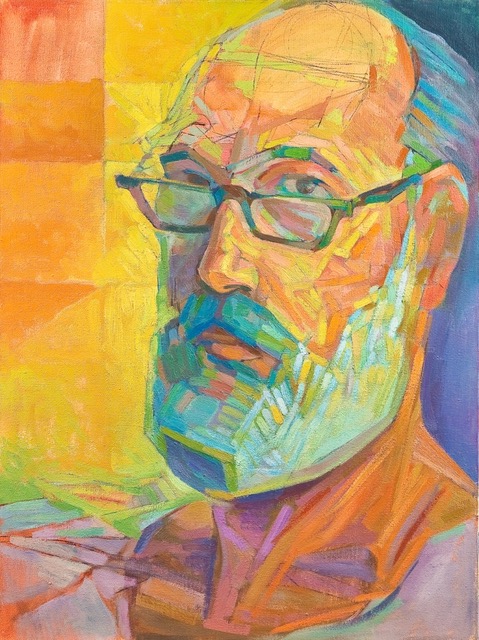

Close to the pub at 95 Kingston Road were homes with rooms to rent. I decided to take my chances. At the first door I knocked on, an elderly man answered. He sported a marvelously bald head with a few strands of hair combed over it, and was smoking a pipe. His name was Ernest Pool. The first thing he said was, “I have no rooms to rent.” I decided he was lying, and said, “My name is Myron Barnstone. I’m an art student. I’m going to be in Oxford for three years.” I had been in town long enough to get an idea of what things were like in the town. I continued, “Unlike most of the undergraduates, I will remain here for three years, so whatever room you rent me I will remain in for the entire time and you won’t have to worry about it.” He was shaking his head no. When he began to close the door, I quickly inserted my foot, and he had me come in.